From Trial & Error to a Robust, Energy-Efficient Pipeline on Jetson Orin Nano Super: Building a natural voice interface for a robot or a cyber-physical system (CPS) is deceptively hard. Speech-to-Text (STT) models like Whisper work extremely well, but running them continuously is inefficient, power-hungry, and often unnecessary.

The goal of most robotics is to design machines that can help and assist humans. Robots are deployed across a broad spectrum of industries to improve productivity, efficiency, and safety. Let’s say, robotics is the interdisciplinary study and practice of the design, construction, operation, and use of robots. Building effective voice interfaces requires understanding not just software, but also the role of electrical power and control systems in robotic and CPS design.

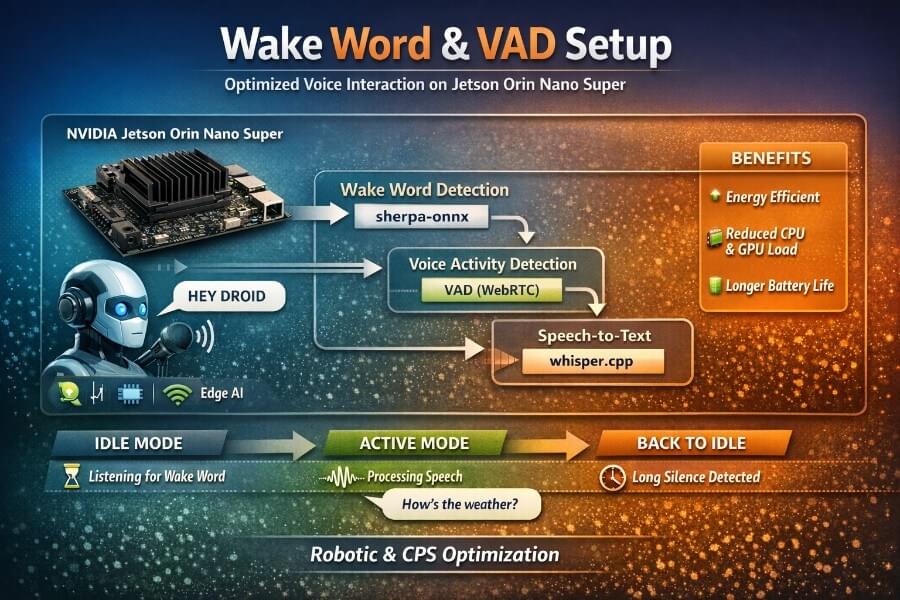

In this article, I share a real, hands-on journey: how I built a reliable Wake Word + VAD (Voice Activity Detection) pipeline in front of whisper.cpp, running locally on a Jetson Orin Nano Super. We’ll go through:

the hardware context (Jetson Orin Nano Super),

the problem with “always-on Whisper”,

multiple failed or sub-optimal wake-word attempts,

why some libraries look good on paper but fail in practice,

how we finally landed on a robust sherpa-onnx + VAD architecture,

and why this matters deeply for energy efficiency in robotics.

This article is technical, but pedagogical. Everything here comes from real debugging sessions, not marketing slides.

1. Hardware Context: Jetson Orin Nano Super

The NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano Super Developer Kit is a compact edge-AI computer designed for robotics and embedded systems. Its small form makes it suitable for integration into various robotic designs, allowing flexibility in the physical structure and configuration of robots.

Key characteristics

CPU: 6-core ARM Cortex-A78AE

GPU: Ampere architecture (up to ~40 TOPS INT8)

Memory: 8 GB LPDDR5

Power envelope: typically 7–15 W

I/O: GPIO, I2C, SPI, USB, CSI camera, audio via ALSA

This board is powerful enough to:

host a local LLM / VLA,

control sensors and actuators.

But it is not a desktop GPU. Every watt matters, especially on battery-powered robots.

2. The Core Problem: Always-On Speech Recognition

The naïve approach to voice interaction is simple:

“Just listen continuously and send audio to Whisper.”

In practice, this is a bad idea:

Whisper inference (even optimized) uses GPU + memory bandwidth.

Continuous inference wastes energy when no one is speaking.

It competes with:

vision pipelines,

local LLM reasoning,

motion control,

perception stacks (ROS 2).

The real requirement

We need a hierarchical audio pipeline:

Idle (ultra-low cost)

→ Just listen for a short keyword.Active (short bursts)

→ Capture speech segments only when needed.Back to idle automatically

→ No wake word repetition during a conversation.

This is where Wake Word + VAD become fundamental building blocks.

Designing Voice User Interfaces

Designing voice user interfaces (VUIs) is a complex, multidisciplinary challenge that sits at the intersection of human-computer interaction, artificial intelligence, and advanced software engineering. At its core, a well-crafted VUI enables users to interact with robots and other cyber-physical systems through natural language, leveraging voice commands and wake words to create a seamless and intuitive user experience.

A successful VUI must do more than simply recognize words, it needs to understand intent, context, and the nuances of human language. This requires integrating sophisticated software components, such as natural language processing algorithms and control systems, to ensure that the robot or device responds appropriately to user input. For example, in collaborative robots working alongside humans on manufacturing floors, a robust VUI allows operators to issue hands-free commands, improving both efficiency and safety by reducing the need for manual controls or graphical user interfaces.

In the realm of humanoid robots and social robots, voice user interfaces play a critical role in enabling natural, conversational interactions. These systems must interpret not only the words spoken but also the intent behind them, adapting their behavior to suit the context and the user’s needs. This level of interaction is essential for building trust and fostering effective human-robot collaboration, especially in environments where robots are expected to perform complex tasks or respond to dynamic situations.

Industrial robots also benefit from advanced VUIs, which can streamline process control and automation by allowing operators to manage machinery and workflows through spoken instructions. This hands-free approach is particularly valuable in environments where safety is paramount and operators need to maintain focus on their surroundings.

However, designing voice user interfaces also introduces significant security risks, especially as robots and smart home technology become more interconnected. Unauthorized access to voice-controlled systems can compromise safety, privacy, and operational integrity. To mitigate these risks, it is essential to implement robust authentication mechanisms, encrypted communication channels, and continuous monitoring for anomalous behavior.

Ultimately, the process of designing voice user interfaces is about more than just technology, it is about creating systems that empower users to interact with robots and devices in ways that are natural, efficient, and secure. By focusing on the integration of artificial intelligence, control systems, and user-centric design principles, we can build VUIs that not only enhance human-robot interaction but also set new standards for safety and usability in the rapidly evolving landscape of robotics and automation.

Human Robot Interaction and Voice Interfaces

Human Robot Interaction (HRI) is at the heart of modern robotics and cyber-physical systems, shaping how humans and robots communicate, collaborate, and coexist. As robots become more deeply intertwined with everyday life, whether as collaborative robots on factory floors, social robots in public spaces, or smart assistants in our homes, the design of intuitive, reliable user interfaces becomes paramount.

One of the most transformative advances in HRI is the rise of voice user interfaces (VUIs). Unlike traditional graphical user interfaces (GUIs), which rely on screens and manual input, voice interfaces enable hands-free, natural communication. This is especially valuable in environments where users need to focus on complex tasks, such as process control in manufacturing, operating industrial robots, or managing smart home technology. By issuing voice commands, users can interact with robotic systems, control devices, and access information without breaking their workflow or compromising safety.

Designing effective voice user interfaces for robots requires a nuanced understanding of both human language and the technical constraints of robotic systems. Creating your own wake word model is a critical step in this process. A custom wake word not only personalizes the interaction, making it more secure and less prone to accidental activation, but also optimizes the system for specific environments, accents, and use cases. For example, a unique wake word can activate a voice assistant in a noisy industrial setting or trigger a mobile robot to listen for instructions in a dynamic environment.

While GUIs remain essential for providing visual feedback and detailed control, they can fall short in scenarios demanding real-time, hands-free interaction. Voice interfaces fill this gap, enabling more fluid and efficient human-machine communication. This is particularly true for collaborative robots (cobots) that work alongside humans, where seamless voice interaction can enhance safety, productivity, and user satisfaction. Humanoid robots, designed to mimic human behavior and facial expressions, also benefit from advanced voice interfaces that support natural dialogue and emotional engagement.

The complexity of robotic systems, spanning control algorithms, mechanical components, and artificial intelligence, means that designing robust voice interfaces is a multidisciplinary challenge. Expertise in computer science, machine learning, software components, and mechanical construction is essential to ensure that voice commands are interpreted accurately and executed safely. Security risks must be carefully managed, especially as robots become connected to other devices and networks in smart homes and industrial environments.

Voice interfaces are not just about convenience; they are about enabling new forms of interaction and automation. In autonomous vehicles, for instance, voice commands can help manage traffic flow and enhance safety. In social robots, voice interaction supports more engaging and empathetic experiences. The integration of text-to-speech, historical data analysis, and real-time decision making further expands the capabilities of modern robotic systems.

As rapid innovation continues to drive the field forward, the future of HRI will depend on our ability to create voice interfaces that are not only technically advanced but also deeply attuned to human needs and behaviors. Whether in manufacturing, healthcare, smart homes, or public spaces, the synergy between humans and robots, enabled by thoughtful voice interface design, will define the next generation of cyber-physical systems.

In summary, the development of wake word models, robust voice activity detection, and seamless voice user interfaces is central to advancing human-robot interaction. By focusing on usability, safety, and adaptability, we can create robotic systems that truly listen, understand, and respond, empowering users and transforming the way we interact with technology.

3. Wake Word: What We Tried (and Why It Failed)

Attempt 1 – Whisper Alone (No Wake Word)

Using only Whisper + silence detection: User speaks → audio accumulates → Whisper inference

Problems:

Latency accumulates (buffering).

Whisper still runs very often.

GPU never really “rests”.

❌ Not acceptable for robotics.

Attempt 2 – openWakeWord (ONNX / TFLite)

openwakeword looks attractive:

fully local,

multiple pretrained keywords (“hey jarvis”, “alexa”, “weather”…),

ONNX/TFLite backends.

In practice, we observed:

extremely low confidence scores on real microphones,

sensitivity to pronunciation and room acoustics,

unstable thresholds,

repeated false negatives.

Example logs during tests:

1 | [AUDIO] rms=800.0 |

Even shouting or using Google Translate TTS often failed.

❌ Technically interesting, but unreliable in real environments.

Attempt 3 – Porcupine (Picovoice)

Porcupine is a well-known commercial wake-word engine.

Pros:

excellent accuracy,

low CPU usage.

Cons (critical for us):

requires API keys,

licensing constraints,

platform limitations (Jetson ARM quirks),

dependency on vendor ecosystem.

For a fully local, autonomous robot, this is a deal-breaker.

❌ Not aligned with a sovereign / offline stack.

4. The Turning Point: sherpa-onnx Keyword Spotting

We finally switched to sherpa-onnx KWS, using a Zipformer-based keyword spotting model.

Why it worked:

fully offline,

runs efficiently on CPU,

supports custom wake words,

same model family used in ASR research,

deterministic behavior once tuned.

Additionally, users can create their own wake words for systems like Home Assistant and Rhasspy, which is an important aspect of designing voice user interfaces to enhance personalization and user experience.

Key insight

The model itself was fine.

The mistake was using it like a frame-by-frame classifier.

The solution was to micro-batch audio, exactly like in offline tests.

5. Micro-Batch Wake Word Detection (The Trick That Made It Work)

Instead of feeding 20 ms frames directly:

we keep a sliding window (e.g. 1.5 s),

every 150 ms, we:

feed the window to the KWS model,

add a short silence pad,

call input_finished() to flush decoding.

This mirrors how keyword spotting is evaluated offline.

Result:

1 | [WAKE] HEY DROID (rms=253.3) -> ACTIVE |

Latency: ~0.8–1.0 s

Accuracy: dramatically higher

This was the breakthrough.

6. Voice Activity Detection (VAD): The Second Pillar

Wake words alone are not enough.

Once the robot is awake, we want:

natural pauses,

multiple sentences,

no repeated “HEY DROID”.

This is the role of VAD.

What is VAD?

VAD classifies short audio frames as:

speech

non-speech (silence / noise)

We used WebRTC VAD, which is:

lightweight,

well-tested,

deterministic,

perfect for 16 kHz mono audio.

How VAD is used here

Power conservation is achieved in on-device implementations of VAD by deactivating intensive processes during periods of silence. VAD is commonly used in various applications such as telecommunication, voice assistants, and automated transcription services. VAD enhances accuracy in speech recognition by filtering out background noise and focusing on relevant audio segments. VAD conserves resources by processing only segments that contain actual speech, saving CPU and bandwidth.

Detect speech start → begin utterance buffer.

Detect short silence (~800 ms) → end of sentence.

Detect long silence (~12 s) → return to IDLE (wake word required again).

This creates a conversation mode:

1 | HEY DROID |

7. Full Audio Pipeline Architecture

1 | [ Microphone ] |

Why this matters for energy efficiency

GPU is idle most of the time.

CPU runs small, cache-friendly models.

Battery life improves significantly.

Thermal headroom remains for vision / planning.

This is exactly what cyber-physical systems need:

intelligence, but only when it matters.

8. Example Commands and Observed Results

Recording a test wake word:

1 | arecord -D plughw:1,0 -f S16_LE -r 16000 -c 1 -d 5 /tmp/hey_droid.wav |

Offline KWS test:

1 | DETECTED: ['HEY DROID', 'HEY DROID'] |

Live pipeline:

1 | [IDLE] Dis 'HEY DROID' |

9. Why Wake Word + VAD Is a Fundamental CPS Pattern

This architecture is not specific to speech.

It is a general CPS design pattern:

low-power sentinels (wake triggers),

high-power reasoning on demand,

automatic return to idle.

You can apply the same idea to:

vision (motion → perception),

radar / lidar,

tactile sensing,

event-driven robotics (including control systems for mobile robots and search applications such as search and rescue robots).

Conclusion

What looks like a “small UX feature” (a wake word) is actually a core systems problem.

By combining:

sherpa-onnx keyword spotting,

WebRTC VAD,

whisper.cpp as an on-demand service,

we built a robust, local, energy-aware voice interface suitable for real robots and cyber-physical systems.

When designing voice user interfaces, it is important to remember that voice user interfaces (VUIs) are designed to allow users to interact with technology through voice commands. Users expect a communication experience similar to talking to another person, so the user interface should provide clear information about what users can do and how to express their intentions. Ambiguity in speech can lead to frustration if the system does not understand commands, so VUIs should be designed to minimize misunderstandings. Limiting the amount of information provided helps avoid overwhelming users, and providing visual feedback, such as LEDs, can enhance the user experience by indicating that the voice user interface is actively listening. These best practices are essential for designing voice user interfaces that are intuitive and effective. The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning launched the field of robotics forward, expanding what is possible for robot automation and autonomy. The future of robotics relies heavily on the advancements of artificial intelligence (AI).

The key lesson is simple:

Don’t make your robot think all the time. Teach it when to think.

In the next articles, we’ll connect this pipeline to:

ROS 2 actions,

GPIO feedback (LEDs / servos),

and higher-level reasoning models.