At CES 2026, Jensen Huang spoke extensively about the concept of Physical AI, AI systems that interact with the physical world (robots, drones, embodied AI, etc.). Physical AI is not fully related to LLMs.

Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have dramatically changed how we design software systems. They can reason over text, plan sequences of actions, interpret ambiguous instructions, and generate structured outputs. As a result, many recent robotics demos show LLMs “controlling” robots directly, issuing movement commands, triggering actuators, or even driving motors in real time.

This is a mistake.

Not because LLMs are weak, but because they are fundamentally the wrong tool for low-level control.

Robots are Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS). CPS are engineered systems that integrate computational elements with physical processes. These engineered systems enable interaction between digital and physical components, driving advancements in sectors such as manufacturing, transportation, healthcare, and energy.

In this article, we will take a clear, engineering-driven position:

LLMs are planners and interpreters, not controllers.

We will explain:

what LLMs are good at, and where they fail

why motor control is a cyber-physical problem, not an AI problem

how latency, hallucinations, and nondeterminism break physical systems

how real robots actually control motors, encoders, and actuators

how to integrate LLMs safely into a CPS architecture

This article is long, technical, and opinionated, by design.

1. What LLMs Are Good At (And What They Are Not)

1.1 What LLMs Excel At

LLMs are probabilistic sequence models trained on massive corpora of human-generated text. As a result, they excel at:

Natural language understanding

Ambiguous intent resolution

High-level reasoning and planning

Tool selection and orchestration

Explaining and summarizing system state

In robotics, this makes them excellent at:

interpreting human commands (“go near the table, but avoid people”)

decomposing tasks (“pick → grasp → place”)

selecting pre-defined skills or behaviors

generating symbolic plans or goals

LLMs operate best in semantic space, not physical space.

1.2 What LLMs Are Fundamentally Bad At

LLMs are not suitable for:

Real-time control loops

Deterministic execution

Safety-critical decisions

Continuous feedback control

High-frequency signal processing

Why?

Because LLMs are:

Non-deterministic (sampling-based outputs)

Stateless unless externally constrained

Slow compared to control-loop requirements

Unaware of physical constraints

Prone to hallucination

These properties are acceptable in planning. They are catastrophic in motor control.

2. Motor Control Is a Cyber-Physical Problem

Robots are Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS). That means they operate at the intersection of:

software

physical dynamics

time

energy

irreversible actions

In CPS, computational processes and the physical environment are deeply intertwined, creating a tight, bidirectional interdependence that enables real-time interaction and feedback. CPS operates in real time and responds to changes in the physical environment with minimal delay. The main components of CPS include sensors, actuators, computational nodes, and communication networks. In robots and industrial applications, CPS often manages continuous processes, such as those found in manufacturing or energy production, ensuring seamless and uninterrupted operations.

A motor does not “try again” if you make a mistake.

2.1 The Control Loop Reality

At the lowest level, robots rely on closed-loop feedback control:

1 | desired_state → controller → actuator → physical system |

This loop runs at:

100 Hz to 10 kHz

with hard timing constraints

under noise, friction, backlash, and inertia

LLMs cannot operate at this level. Even a 50 ms delay can destabilize a system.

2.2 Determinism Matters

Motor controllers must:

produce the same output for the same input

meet strict deadlines

remain stable under perturbation

LLMs:

may produce different outputs for identical prompts

cannot guarantee bounded execution time

cannot be formally verified for stability

This alone disqualifies them from motor control.

3. How Robots Actually Control Motors and Actuators

To understand why LLMs should not control motors, we must understand what actually does. Cyber physical systems (CPS) consist of heterogeneous components, including sensors, actuators, processors, and communication devices. A typical CPS architecture includes physical processes, sensors, communication networks, computational nodes, actuators, and control algorithms, all interconnected through robust communication to ensure seamless operation and integration.

3.1 Hardware Control Stack

A real robot control stack looks like this:

1 | LLM / Planner (Hz) |

Cyber-physical systems (CPS) rely on data collected from sensors and other sources, such as networked devices or external databases, to make informed decisions and adapt to changing conditions in real time.

Each layer exists for a reason.

3.2 Motor Drivers and Microcontrollers

Motors are not driven by Linux processes.

They are driven by:

microcontrollers (MCUs)

motor drivers (H-bridges, ESCs; different motor drivers use different power control technology, such as SCR or PWM, to regulate motor operation)

real-time firmware

These components:

read encoders

regulate current and torque

enforce hardware limits

run without an OS or with RTOS

Typical control loops include:

current loop

velocity loop

position loop

Each loop must be stable and bounded.

3.3 Encoders and Feedback

Encoders provide:

position

velocity

sometimes torque estimation

Feedback is:

noisy

delayed

imperfect

Controllers (PID, MPC, etc.) exist to compensate for reality, not idealized models.

An LLM has no concept of:

friction

saturation

thermal limits

backlash

sensor noise

4. Why LLMs Fail as Controllers

4.1 Latency Kills Stability

A stable controller must react within a predictable time window.

LLM inference:

varies with system load

varies with prompt length

varies with hardware

may spike unpredictably

A delayed command is often worse than no command.

4.2 Hallucinations Are Physical Hazards

In software, hallucinations are annoying.

In robotics, they are dangerous.

Examples:

hallucinated joint limits

imaginary obstacles

incorrect coordinate frames

wrong units (meters vs centimeters)

A hallucinated motor command can damage hardware, or people.

4.3 No Formal Guarantees

Control systems rely on:

stability analysis

bounded inputs/outputs

safety envelopes

LLMs provide none of these guarantees.

You cannot prove an LLM-controlled robot is safe.

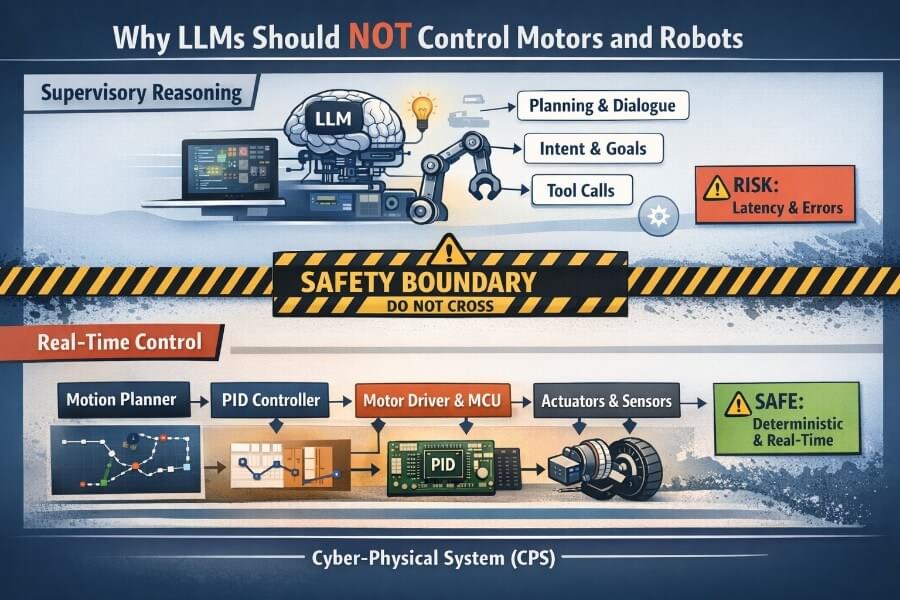

5. Supervisory vs Operational Layers

This distinction is critical.

5.1 Operational Layer (Hard Real-Time)

This layer:

controls motors

reads sensors

enforces safety

must never block

Examples:

real-time motion planners

firmware-level safety checks

LLMs must never operate here.

5.2 Supervisory Layer (Soft Real-Time)

This is where LLMs shine.

Responsibilities:

interpreting human intent

selecting behaviors

generating goals

explaining decisions

This layer can tolerate:

latency

uncertainty

probabilistic outputs

6. Tool Calling as a Safety Boundary

The correct integration pattern is tool calling.

6.1 LLM as a Planner, Not an Executor

Instead of:

“Rotate motor A at 120 RPM”

The LLM should say:

“Execute move_arm_to_pose(x, y, z)”

The tool:

validates inputs

checks constraints

executes deterministically

reports status

6.2 Tools as Contracts

Each tool:

has a strict schema

enforces limits

rejects unsafe requests

This turns the LLM into:

a decision maker

not a direct actuator

7. Real-World Failure Scenarios

Scenario 1: Latency Spike

An LLM inference stalls for 300 ms during a balancing maneuver → robot falls.

Scenario 2: Unit Hallucination

LLM outputs “move 10” assuming centimeters → system interprets meters → collision.

Scenario 3: Context Drift

LLM forgets current joint state → sends incompatible command.

These failures are not hypothetical, they are inevitable.

8. A Sane Integration Pattern for CPS Robots

8.1 Recommended Architecture

1 | Human |

9. System Design Considerations

Designing robust robotic control systems requires a holistic approach that balances performance, reliability, and safety. The selection of motor control systems, such as servo motors for precise speed control or stepper motors for accurate positioning, should be tailored to the specific demands of the application, whether in industrial control systems, robotic surgery, or other automation systems. Choosing between open-loop and closed-loop control systems is critical; for example, closed-loop systems are essential in environments where real-time feedback and adaptability to changing conditions are required.

Integration of advanced software components, including artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, can significantly enhance the adaptability and efficiency of control systems. These technologies enable the system to monitor its physical environment, adjust to fluctuations in supply voltage, and optimize performance in real time. Environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and power supply stability must also be considered to ensure that all components operate reliably under expected conditions.

A well-designed user interface is another key element, providing operators with intuitive controls and clear feedback on system status. This facilitates not only day-to-day operation but also maintenance and troubleshooting, reducing the risk of human error. Ultimately, successful system design hinges on the seamless integration of hardware and software components, ensuring that the system can operate safely and efficiently in its intended physical environment.

10. Testing and Validation Procedures

Comprehensive testing and validation are essential to ensure that robotic control systems meet stringent performance, safety, and reliability standards. This process begins with verifying that all individual components, such as the motor controller, sensors, and software modules, function correctly and interact seamlessly within the overall system. Testing should encompass a wide range of scenarios, including variations in input voltage, load conditions, and environmental factors, to assess the system’s robustness and adaptability.

Utilizing both historical data and real-time data collection allows engineers to fine-tune system parameters, optimize performance, and identify potential weaknesses. Adhering to industry standards and regulations, particularly those governing safety and security systems, is crucial for compliance and risk mitigation. Human interaction should be incorporated into the testing process to evaluate the usability of the system and ensure that the user interface supports efficient operation and quick response to anomalies.

By following rigorous testing and validation procedures, developers can ensure that their control systems are ready for deployment in demanding environments such as manufacturing, healthcare, and transportation. This approach not only enhances safety and efficiency but also builds confidence in the system’s ability to perform reliably under real-world conditions.

11. Maintenance and Repair Procedures

Ongoing maintenance and prompt repair are vital for maximizing the lifespan and reliability of robotic control systems. Regular inspections of key components, including motors, sensors, and software, help detect early signs of wear, malfunction, or performance degradation. Monitoring critical metrics such as speed control, torque, and overall system efficiency, and comparing them against historical data, enables proactive identification of issues before they escalate.

Software updates are equally important, ensuring that the system benefits from the latest security enhancements and performance improvements. Well-documented repair procedures, including step-by-step guides for replacing faulty components or troubleshooting complex problems, empower users to address issues quickly and effectively. The use of auxiliary contacts and other devices can streamline maintenance by providing temporary workarounds or facilitating diagnostics.

Training and support for users are also essential, enabling them to perform routine maintenance and basic repairs, which helps minimize downtime and maintain high system availability. By prioritizing regular maintenance and efficient repair processes, organizations can ensure that their control systems continue to deliver optimal performance and safety across a range of applications.

12. Troubleshooting Procedures

A systematic approach to troubleshooting is crucial for maintaining the performance and reliability of robotic control systems. Effective troubleshooting begins with comprehensive data collection, drawing on sensor data, process data, and historical records to identify patterns and pinpoint the root cause of issues. Analyzing this information helps distinguish between hardware faults, software glitches, and external influences such as fluctuations in supply voltage or changes in the physical environment.

Incorporating artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques can further enhance fault detection and diagnosis, enabling predictive maintenance and reducing the risk of unexpected failures. Quality control processes should be integrated into troubleshooting workflows to ensure that any corrective actions restore the system to its expected performance benchmarks.

By following structured troubleshooting procedures, developers and operators can quickly resolve issues, minimize downtime, and maintain high standards of safety and efficiency. This approach is essential for ensuring that control systems continue to operate reliably in diverse and dynamic environments.

13. Future Developments and Emerging Trends

The landscape of robotic control systems is rapidly advancing, fueled by breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, machine learning, and the proliferation of IoT devices. Future developments will emphasize the creation of more autonomous and intelligent systems capable of managing complex tasks in dynamic environments such as civil infrastructure, healthcare, and transportation. The integration of CPS technologies, combining computational elements with physical processes, will enable real-time data collection, analysis, and decision-making, driving improvements in system responsiveness and adaptability.

Emerging trends like edge computing and 5G connectivity are set to revolutionize control systems by providing faster data transfer, lower latency, and enhanced connectivity between devices. As these technologies mature, security systems and data protection will become even more critical, prompting the development of robust, resilient architectures capable of detecting and mitigating cyber threats in real time.

These advancements will lead to significant gains in areas such as traffic flow optimization, energy efficiency, and quality control, ultimately enhancing safety, productivity, and sustainability across different industries. As control systems continue to evolve, their integration with advanced computational elements and real-time data capabilities will unlock new possibilities for automation, resource management, and intelligent decision-making in the physical world.

9. Key Takeaways

LLMs are not controllers

Motor control is a real-time CPS problem

Safety requires determinism and constraints

LLMs belong in supervisory layers

Tool calling is the correct abstraction boundary

10. The Rise of Physical AI and the Broader AI-Driven Robotics Ecosystem

A major theme emerging from CES 2026 is what the industry now calls “Physical AI”, the idea that AI is transitioning from software-only reasoning to systems that perceive, decide, and act within the physical world. Unlike earlier waves that focused on chatbots or generative text, Physical AI embeds intelligence directly into robots, vehicles, drones, and other autonomous machines.

10.1 What Physical AI Really Means

At CES 2026, dozens of exhibitors and keynote presentations made it clear that AI models are now being designed to handle physical embodiment, not just digital tasks. This includes:

Humanoid robots capable of industrial and logistics work (e.g., updated Atlas platforms designed for factory sequencing and manipulation).

AI-enabled home and service robots that go beyond vacuuming, with perception, planning, and action tightly integrated.

Wearables and exoskeletons that augment human movement using real-time AI terrain understanding.

Autonomous vehicles and robotaxis with AI stacks trained in virtual environments to anticipate rare edge cases.

In this context, Physical AI refers not just to perception and reasoning but to continuous, high-frequency decision-making fused with real-world actuation under hard constraints. This is a significant leap from traditional robotics, emphasizing tight feedback loops, prediction, and adaptability within environments the system has never seen before.

10.2 Beyond LLMs: Vision-Language-Action and Robotics Foundation Models

Another important trend at CES 2026 is the rise of specialized multimodal models, sometimes called Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models, designed specifically for physical systems. These models aim to interpret diverse sensory inputs (vision, lidar, audio) and generate structured actions that can interface cleanly with robot planners and control stacks.

Major platform announcements (e.g., NVIDIA’s new reasoning ecosystem and foundational models tailored for physical tasks) indicate that the next generation of robotics AI will not be simple adaptations of LLMs, but rather architectures that bridge perception, cognition, and planning in a way that respects physics and real-world constraints.

10.3 How Physical AI Enhances (But Should Not Replace) Core CPS Control

Even in this emerging landscape, the fundamental lessons from this article hold:

Physical AI models can inform and adapt high-level strategy, but they must still be decoupled from low-level control loops.

Robots must continue to rely on deterministic controllers (e.g., PID, MPC) for actuation and stability.

Integrations should preserve safety boundaries through validated “skill execution” tools rather than permitting an AI system to manipulate actuators directly.

What is changing is the scope of high-level autonomy: rather than merely planning sequences of behaviors, Physical AI systems increasingly aim to learn and refine goals based on continuous sensory feedback. This places new demands on architecture, including better simulation environments, digital twins, and edge inference hardware to support real-time constraints.

10.4 A Broader Ecosystem, Robots, Drones, and Beyond

While robotics dominated the physical AI narrative at CES 2026, adjacent domains are adopting similar principles:

Autonomous drones and aerial vehicles increasingly combine AI vision with real-time path planning and collision avoidance.

Autonomous ground vehicles and robotaxis apply physical AI to complex navigation and dynamic scene interpretation.

Industrial machines and construction automation embed AI for tool manipulation, environment mapping, and adaptive planning.

The common thread across these systems, whether humanoid robots, drones, or autonomous vehicles, is the fusion of perception, reasoning, and action within time-critical physical environments.

In summary: the CES 2026 “Physical AI” trend illustrates that AI is no longer confined to screens or static datasets, it is increasingly embodied, requiring careful architectural designs that respect the same CPS principles we’ve discussed throughout this article. The challenge is not to hand control to AI unfiltered, but to integrate these powerful reasoning capabilities into supervisory layers that feed well-defined, safe control pipelines.

Conclusion

The future of robotics and Physical AI is not “LLMs controlling motors”.

It is LLMs collaborating with classical control systems, each doing what they do best.

Robots that work in the real world will always be:

grounded in physics

constrained by time

stabilized by control theory

LLMs can reason about the world.

Controllers must survive in it.

That distinction matters.